Education Majors Fear Unpreparedness for In-person Instruction Will Lead to Disconnect in the Classroom

The Little Rebellion | The New Paltz Voice | Austin Kong

Learners of all ages are experiencing a massive upheaval in our education system. From remote classes held on Zoom to socially distanced classrooms, nobody is learning the same way—and some students have checked out entirely. For college students majoring in primary education, this drastic change is more than just a tweak in curriculum.

Education majors are expected to do their fieldwork by student-teaching a class alongside a cooperating teacher. This experience helps them build confidence and character as well as bonding with children in the classroom, which is an integral part of their final year in college.

Teachers Trained Online: Are They Ready?

Max Hodson, a former art education student at SUNY New Paltz, was teaching both online and in-person at a middle school in Newburgh in spring 2021. His cooperating teacher ran a very tight ship in their school, which gave him limited freedom to do what he wanted.

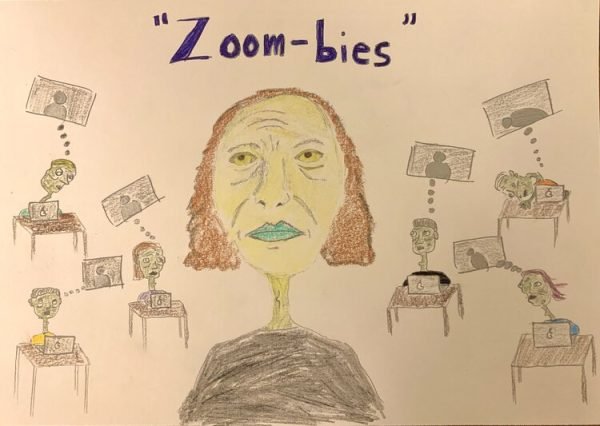

Hodson expressed dismay at the morale of his students in their school work and especially in Zoom calls where young middle schoolers are expected to pay attention to their screens like they would in a normal classroom and submit their homework online. He described a disconnect in his students having to sit first thing in the morning and stare at computers all day, which isn’t conducive to the creativity students should have in order to create art. He believed that was not a realistic standard and definitely not one for young pupils. He often had to do volume control or ask repeated questions like: “Students, what do you think?” or “Can you read this?” or even “Can someone just say anything?” echoing his own voice with no response. Parents didn’t want to risk their child attending classes in-person, he said, so only a few showed up while the rest of the seats were barren. “There are kids that don’t come at all, like their parents said ‘no, they’re staying home.’ And I understand that.”

Hodson was also expected to record his lessons, come up with lesson plans and know tech-savvy things like various formats of Google programs and their applications. “There are so many different forms of Google I didn’t even know existed.”

He saw CDC guidelines first-hand in place in school. Lunch time is mirrored like class with desks spaced six feet apart and a Netflix movie playing on a smart board in the front of the cafeteria. “It was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen,” said Hodson. “Some even had their school laptops open.” When discussing their mindset, he said, “I think the word my teacher used was shell shock. I mean, a bit of an overkill, but still pretty accurate to how zombie-like these kids are.”

He often had to do volume control or ask repeated questions like; "Students, what do you think?" or "Can you read this?" or even "Can someone just say anything?" echoing his own voice with no response. - Max Hudson

Educator Struggle in the Transition from In-Person to Remote Learning

Diana Di Rico spoke to the struggles of virtual teaching, saying, “connections between students are hard to foster or maintain. Many of them feel extremely isolated from one another and they’re having a very hard time opening up.”

Pivoting to online classes was no easier for the teachers than it was for education majors. Diana Di Rico has taught at Baruch College Campus High School as an English teacher for 16 years. She agreed, like many others, that “connections between students are hard to foster or maintain. Many of them feel extremely isolated from one another and they’re having a very hard time opening up.”

Di Rico had to shift the dynamic of her classroom entirely because her students weren’t always comfortable with having their cameras turned on in Zoom or even speaking through the mic. For students who were struggling due to a weak internet connection or attending class from a different part of the world, she had the realization that some might fail. Thus she had to become increasingly flexible as an educator. “Fostering accountability isn’t different now. How to hold people accountable while being flexible and meet them where their mental health remains front and center, is what’s different. It’s something on my mind as a high school teacher.”

In one instance, she described how disconnected she felt from her students when they could recognize her, but she didn’t know any of their faces due to the greyed out boxes she saw in her Zoom class. As she collected paperwork in her school, a young man, who never usually attended in-person, entered her classroom and recognized her but she didn’t know who he was. It was only until he said his name that prompted a jolt in her memory and she came to a realization that she knew him. That was the first time they actually met. “I’ve never seen this young man who, on my end, he sees me everyday.”

“There’s also no opportunity [for students] to be silly, to joke, to flirt, or to meet someone new,” she said.

Despite all of this, she tried to remain resilient and put on a positive face everyday. “I think a lot of the reason people stay in teaching is because it can be extremely rewarding. And the rewards have largely been taken out. So, to sustain it, I have to constantly look to see where it’s been working.”.

While education undergrads like Max have had a more extensive teaching experience with both online and in-person, some others were not so lucky with that opportunity.

“Connections between students are hard to foster or maintain. Many of them feel extremely isolated from one another and they're having a very hard time opening up.” - Diana Di Rico

Scott, a SUNY New Paltz adolescent education major, who preferred not to use his complete name, had his entire teaching placement stalled for about a month with nothing to do during the beginning of his spring semester. In the spring of 2021, he began teaching at a BOCES school (Board of Cooperative Educational Services). “Having to wait without really being able to ask anything has been a bit stressful because you know that you’re being told, well—it’s COVID,” he said.

Scott knew it was no fault of the school. “At the end of the day, it is out of your control.” He also explained the dilemma of fieldwork at this time. “How could they allow a college student to come to their school and be in a classroom full of kids, and not add to their COVID-19 risk when they already have a high one because it’s a school?”

Even though it was virtual and he didn’t see any of his students in-person, he found that being online worked to his benefit regardless. “I’m still working with my cooperating teacher and making lesson plans. I’m gaining the experience I need to gain.”

Pre-pandemic, he would make slideshows for a lesson on U.S. imperialism, along with some help from his cooperating teacher who would send several links that he could use. This type of lesson plan can be done online, yet he admitted it was limiting. “I have a good amount of resources as it is, but I’d be able to do more traditional lesson plans if the pandemic didn’t happen.”

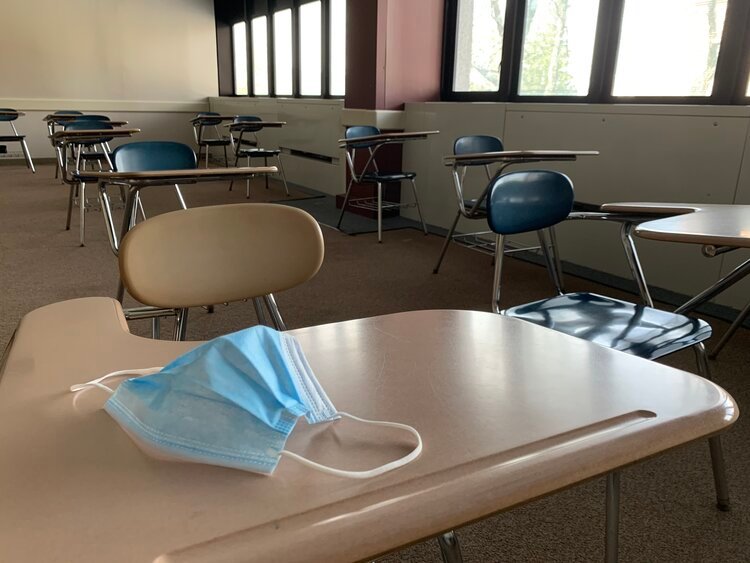

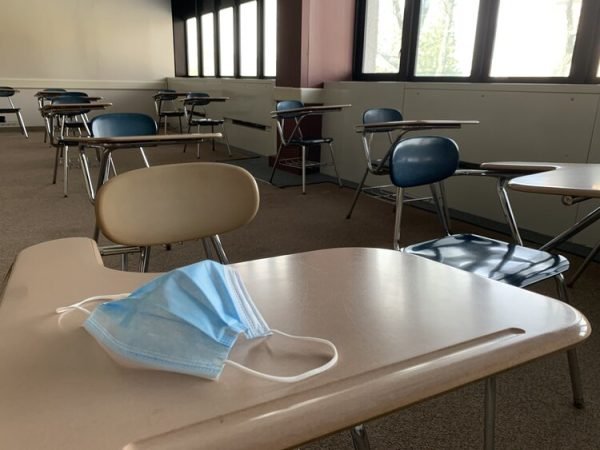

Classrooms at SUNY New Paltz are being used as storage spaces as a result of the college switching to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

No One Feels Prepared

While some students felt that their online fieldwork was enough training, college professors like William Hong, who teaches filmmaking at SUNY New Paltz, weren’t entirely sure. When asked if he felt that students doing their fieldwork are adequately prepared for a future as an educator, he said, “no. I’m not an expert in training teachers, that’s not my field, but there’s something that is vital. I think that if it is not part of the equation, if there isn’t some kind of in-person component at some point—well, I don’t think anyone on this campus would be a teacher if it was 100% remote.”

Sophie Herman, an education undergraduate with a concentration in art history, felt more positively about her experience, but that might have been due to luck in her placement at an elementary school in Marlborough. “I’m one of the lucky ones. I get to come in four days a week,” she said.

Yet in-person teaching can prove to be quite challenging. In a kindergarten classroom, she wasn’t allowed to touch the students or even give them guidance. “Kindergarteners are very tactile and their motor skills are still developing, like learning how to hold pencils and when you can’t use playdough or sensory tables because everyone else is touching it too, it can be challenging. So I don’t know if kids are going to be stunted in that area.”

Even though Herman was limited due to the school’s strict no-touching policy, she felt optimistic because she found ways to excel in other areas. “There’s a trade-off,” she said. “I don’t get the traditional experience, but now I’m awesome at creating slides.”

Stepping up to be a teacher can be strange for someone who hasn’t put in the years. That transition can be nerve-racking especially for a college student. “All of sudden, you’re an adult or an equal and that’s super strange because you’re stepping into their territory,” she said. “I compare it to almost like a stepmother, so that my students won’t be too surprised.”

Will Education Ever Be the Same?

Maya Projansky is a fifth grade teacher in New York City at a public institution called The Earth School. She has taught in an elementary school for 17 years and at a graduate-level teaching course at SUNY New Paltz. For online learning, she felt that it wasn’t normal, especially for her fifth graders. “There’s a neurological need to use the hands when teaching elementary school,” she said.

The biggest challenge for Projansky in this climate was the inability to build proper relationships with students. Online learning shut off all the little things that instructors take for granted in a normal classroom. “We rely on being able to read facial expressions, to catch the tone of voice, the look of an eye, or even body language. And when students don’t have their camera on, I feel like I’m teaching with one arm behind my back.”

Projansky believed that the effects of the pandemic had completely shifted the way educators like herself view normalcy now. “I don’t know that we’ll ever return to normal. And I want to say that, in education, I don’t know if we should return to a full normal,” she said. “A lot of our education structure is built on the Industrial Revolution as a model, rather than the reality of life.”